A four-part series on Fire Departments and Emergency Medical Services in the Field, originally published in Plumas News in 2014 and 2015.

by Tom Forster

Fire Departments and Emergency Medical Services 101, Part I

Why does your local fire department respond if you need emergency medical care? Why do they usually come with a fire engine in addition to the ambulance? Ever wonder what an “EMT” is? How about a “First Responder”? And what about a “Paramedic”? How do our local firefighters fit into these roles in Plumas County? And, perhaps the most important question, why is your local fire department even providing this service?

Fire service roots in providing emergency medical aid go very deep, and can be traced at least as far back as the middle ages. The Knights of Malta became a charitable, non-military organization during the 11th and 12th centuries, providing aid to the sick and poor and helping to set up numerous hospitals. They would later join the Knights of the Crusades in battles to win back the Holy Land.

They wore crimson-colored capes over suits of armor. This provided a defense against fire, one of the newest weapons of war. As invading forces attacked a castle, the defenders would throw down containers of naphtha and other flammable liquids from above. Once the attackers were soaked, a torch would be hurled on them, igniting the fuel-soaked clothing. With their fellow troops then on fire, the Knights of Malta would approach on horseback, rip off their capes, and use them to extinguish the flames on their burning fellow soldiers.

As a reward for their bravery, the Maltese cross worn by the Knights was decorated and inscribed by admirers. It came to be known as one of the most honorable badges for a uniform. The legend of the Maltese cross grew as it became associated with the qualities of loyalty, bravery and defender of the weak. Today, firefighters across the country often wear versions of the Maltese cross on their uniforms and apparatus. A related group was known as the Knights Hospitaller, with links to an ancient hospital system. Spaces limitations here prevent a more detailed description, but those interested can easily find more information on the Internet and in your local library.

The involvement of the American fire service in field medical care or transport can be traced far back in American history, including in the Civil War. It was common for volunteer firefighters of the day to enlist in the Armies of the north and south with soldier groups known as Fire Zouaves. For example, the Battle of Gettysburg memorials recognize among others the 73rd New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, or “2nd Fire Zouaves”. The monument includes a statue of a firefighter standing next to a soldier, with the motto “Firefighters in Peace, Soldiers in War.” While they were not alone in doing so, Fire Zouaves operated field ambulances.

Prior to 1970, attendants with basic or advanced first aid training typically staffed ambulances in America. Often they were volunteer firefighters. Sometimes the ambulances were privately owned or through hospitals, and sometimes they were staffed by fire departments or specialized rescue squads. Fire departments typically focused on fighting fires, but often provided some limited first aid and rescue services. There were and still are some volunteer groups that just do EMS.

As urban areas expanded in the industrial revolution, private industry began to operate many medical ambulance services when there was enough volume to make it profitable. Rural and poor areas where the need was less frequent often did so through volunteer fire departments or specialized rescue squads. In Plumas County, several local fire departments started providing ambulance transport services no later than the 1930’s. This included for example, the Chester, Greenville, Portola, and Quincy volunteer fire departments. Volunteer firefighters, then typically called “firemen”, staffed the units when needed.

By the 1960’s, the experiences of treating wounded soldiers in Korea and Vietnam led researchers to study trauma survival rates, based on emergency care. To their surprise, they found that soldiers who were seriously wounded in Vietnam had a better survival rate than people who were injured in vehicle accidents on California freeways and highways.

This was linked to a number of differences, including a new type of medical corpsman used in Vietnam, trained to perform some advanced procedures such as airway management and fluid replacement. The report, published in 1966 by the National Academy of Sciences, was titled “Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society.” Also in 1966, Congress passed legislation creating the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), from which came the first federal standards for Emergency Medical Services (EMS). By 1967, several large urban areas were developing advanced field emergency medical care programs using firefighters, including Miami, Seattle, Los Angeles, and Pittsburgh.

Pittsburg’s Peter Safar is considered the father of Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR). He began training unemployed African-American men in 1967 to serve in what became the Freedom House Ambulance Service, the first “Paramedics” in the U.S., a more advanced form of training like the Army field medics. The first Los Angeles County Fire Rescue unit, Squad 59, officially went into service on December 8, 1969 with two newly trained Paramedics, leading eventually to an idea from producer Jack Webb to feature FD paramedics in a television show.

When the show “Emergency” first aired in 1972, there were only three pilot paramedic programs operating in America. By the time the show ended in 1977, there were paramedics operating in every state. California was the first state to adopt legislation in 1970 defining paramedic “certification” to provide advanced medical life support, when then Governor Ronald Reagan signed into law the Wedworth-Townsend Paramedic Act.

Why the link to fire departments (FD’s)? Part of the ‘lessons learned’ in Vietnam included the importance of rapid care and transport. Also, emergency medical care incidents in the field sometimes occur with rescue or extrication complications. For example, home fires, car wrecks, and other incidents may first require victims be removed from further danger. Fire Departments can often get there the quickest, and also have the specialized rescue training and equipment for extrication.

Why does your local fire department respond if you need emergency medical care? Why do they usually come with a fire engine in addition to the ambulance? Ever wonder what an “EMT” is? How about a “First Responder”? And what about a “Paramedic”? How do our local firefighters fit into these roles in Plumas County? And, perhaps the most important question, why is your local fire department even providing this service?

Fire service roots in providing emergency medical aid go very deep, and can be traced at least as far back as the middle ages. The Knights of Malta became a charitable, non-military organization during the 11th and 12th centuries, providing aid to the sick and poor and helping to set up numerous hospitals. They would later join the Knights of the Crusades in battles to win back the Holy Land.

They wore crimson-colored capes over suits of armor. This provided a defense against fire, one of the newest weapons of war. As invading forces attacked a castle, the defenders would throw down containers of naphtha and other flammable liquids from above. Once the attackers were soaked, a torch would be hurled on them, igniting the fuel-soaked clothing. With their fellow troops then on fire, the Knights of Malta would approach on horseback, rip off their capes, and use them to extinguish the flames on their burning fellow soldiers.

As a reward for their bravery, the Maltese cross worn by the Knights was decorated and inscribed by admirers. It came to be known as one of the most honorable badges for a uniform. The legend of the Maltese cross grew as it became associated with the qualities of loyalty, bravery and defender of the weak. Today, firefighters across the country often wear versions of the Maltese cross on their uniforms and apparatus. A related group was known as the Knights Hospitaller, with links to an ancient hospital system. Spaces limitations here prevent a more detailed description, but those interested can easily find more information on the Internet and in your local library.

The involvement of the American fire service in field medical care or transport can be traced far back in American history, including in the Civil War. It was common for volunteer firefighters of the day to enlist in the Armies of the north and south with soldier groups known as Fire Zouaves. For example, the Battle of Gettysburg memorials recognize among others the 73rd New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, or “2nd Fire Zouaves”. The monument includes a statue of a firefighter standing next to a soldier, with the motto “Firefighters in Peace, Soldiers in War.” While they were not alone in doing so, Fire Zouaves operated field ambulances.

Prior to 1970, attendants with basic or advanced first aid training typically staffed ambulances in America. Often they were volunteer firefighters. Sometimes the ambulances were privately owned or through hospitals, and sometimes they were staffed by fire departments or specialized rescue squads. Fire departments typically focused on fighting fires, but often provided some limited first aid and rescue services. There were and still are some volunteer groups that just do EMS.

As urban areas expanded in the industrial revolution, private industry began to operate many medical ambulance services when there was enough volume to make it profitable. Rural and poor areas where the need was less frequent often did so through volunteer fire departments or specialized rescue squads. In Plumas County, several local fire departments started providing ambulance transport services no later than the 1930’s. This included for example, the Chester, Greenville, Portola, and Quincy volunteer fire departments. Volunteer firefighters, then typically called “firemen”, staffed the units when needed.

By the 1960’s, the experiences of treating wounded soldiers in Korea and Vietnam led researchers to study trauma survival rates, based on emergency care. To their surprise, they found that soldiers who were seriously wounded in Vietnam had a better survival rate than people who were injured in vehicle accidents on California freeways and highways.

This was linked to a number of differences, including a new type of medical corpsman used in Vietnam, trained to perform some advanced procedures such as airway management and fluid replacement. The report, published in 1966 by the National Academy of Sciences, was titled “Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society.” Also in 1966, Congress passed legislation creating the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), from which came the first federal standards for Emergency Medical Services (EMS). By 1967, several large urban areas were developing advanced field emergency medical care programs using firefighters, including Miami, Seattle, Los Angeles, and Pittsburgh.

Pittsburg’s Peter Safar is considered the father of Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR). He began training unemployed African-American men in 1967 to serve in what became the Freedom House Ambulance Service, the first “Paramedics” in the U.S., a more advanced form of training like the Army field medics. The first Los Angeles County Fire Rescue unit, Squad 59, officially went into service on December 8, 1969 with two newly trained Paramedics, leading eventually to an idea from producer Jack Webb to feature FD paramedics in a television show.

When the show “Emergency” first aired in 1972, there were only three pilot paramedic programs operating in America. By the time the show ended in 1977, there were paramedics operating in every state. California was the first state to adopt legislation in 1970 defining paramedic “certification” to provide advanced medical life support, when then Governor Ronald Reagan signed into law the Wedworth-Townsend Paramedic Act.

Why the link to fire departments (FD’s)? Part of the ‘lessons learned’ in Vietnam included the importance of rapid care and transport. Also, emergency medical care incidents in the field sometimes occur with rescue or extrication complications. For example, home fires, car wrecks, and other incidents may first require victims be removed from further danger. Fire Departments can often get there the quickest, and also have the specialized rescue training and equipment for extrication.

Fire Departments and Emergency Medical Services 101, Part 2

In our last column we described the roots of fire service involvement in providing emergency medical care (EMS) in the field, also known as the ‘pre-hospital setting’. While the fire service is one of many organizations that provide emergency medical care, this column seeks to help you understand your local fire department - EMS incidents usually rank as the largest component of FD responses each year.

Nationally, many consider the publication of the National Academy of Sciences report in 1966 titled “Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society” to be the beginning what has become modern Emergency Medical Care, or EMS. The report identified accidental injuries as “…the leading cause of death in the first half of life’s span,” revealed that in 1965 alone, more Americans died in automobile accidents than died in the entire Korean War.

What became known as “The White Paper” indicated that, outside of the hospital setting, “…if seriously wounded…chances of survival would be better in the zone of combat than on the average city street.” The lack of regulations or standards for ambulance operations and provider training was cited as one of the main reasons for that reality. Several recommendations for the prevention and management of accidental injuries were made, including the standardization of emergency training for “rescue squad personnel, policemen, firemen and ambulance attendants.” This led to the first nationally recognized and standardized curriculum for EMS, Emergency Medical Technician–Ambulance (EMT-A), published in 1969.

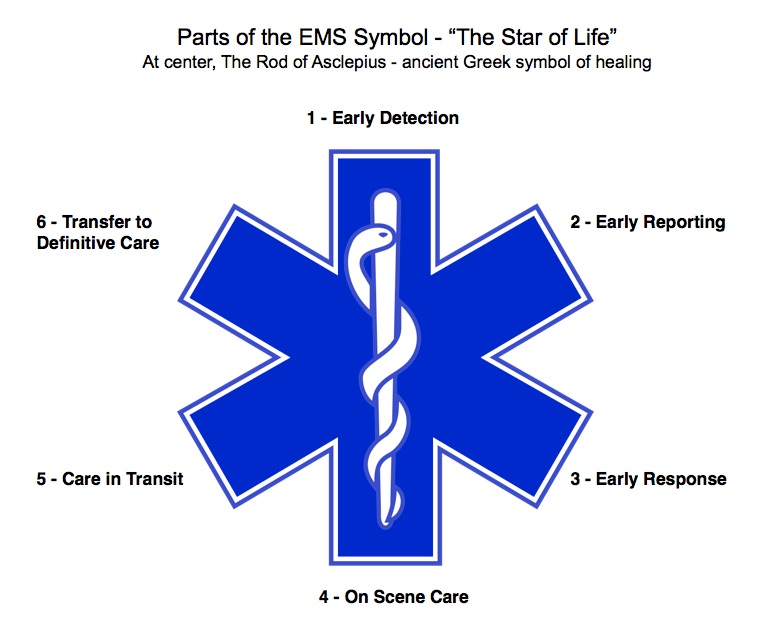

Ever since, a greatly improved EMS system evolved, seeking to improve survival through a chain of actions that starts hopefully with prevention and safety programs, but may end up with care in a hospital emergency room. In between, the blue and white, six-pointed EMS symbol called “the Star of Life” best illustrates the ideal components. It was originally designed by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Traditionally the logo is used as a stamp of identification for ambulances, paramedics, or other personnel such as firefighters trained in EMS. See the illustration accompanying this article for the six parts of EMS. Local FD’s are usually involved in the parts of the Star of Life illustration above in part three (early response) and part four (on scene care), and sometimes in parts five (care in transit) and six (transfer to definitive care).

The licensing of EMS personnel and services occurs at the state level and, for some certifications, at the local level. Each state can add or subtract levels as they see fit for their needs. The federal government identifies a model scope of practice, including minimum skills for Emergency Medical Responders (EMR’s), Emergency Medical Technicians (EMT’s), Advanced EMTs and Paramedics.

In California, there are generally five levels of certification: 1) EMR’s, with a minimum of 40 hours of training; 2) EMT’s, with a minimum of 120 hours of training including some clinical time; 3) Advanced EMT’s (AEMT’s), with a minimum of 88 more hours of training; 4) Paramedics, with an average of 1100 hours of training including much clinical time; and 4) Mobile Intensive Care Nurses (MICN’s), or Registered Nurses who have completed additional training in pre-hospital care and often serve in critical care roles such as air transport. Not all counties offer or support all of these levels of certification.

While states are able to set their own additional requirements for state certification, a quasi-national certification group exists in the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT). The NREMT offers national certification based on the NHTSA National Standard Curriculum for the levels of EMR, EMT, Advanced EMT and Paramedic.

There have been many people who have made contributions to the growth of modern EMS in Plumas County. In Part III of this series, we’ll look closer at some of the early key players and groups, including identifying the first Paramedic and the first Mobile Intensive Care Nurse to serve full-time here.

In our last column we described the roots of fire service involvement in providing emergency medical care (EMS) in the field, also known as the ‘pre-hospital setting’. While the fire service is one of many organizations that provide emergency medical care, this column seeks to help you understand your local fire department - EMS incidents usually rank as the largest component of FD responses each year.

Nationally, many consider the publication of the National Academy of Sciences report in 1966 titled “Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society” to be the beginning what has become modern Emergency Medical Care, or EMS. The report identified accidental injuries as “…the leading cause of death in the first half of life’s span,” revealed that in 1965 alone, more Americans died in automobile accidents than died in the entire Korean War.

What became known as “The White Paper” indicated that, outside of the hospital setting, “…if seriously wounded…chances of survival would be better in the zone of combat than on the average city street.” The lack of regulations or standards for ambulance operations and provider training was cited as one of the main reasons for that reality. Several recommendations for the prevention and management of accidental injuries were made, including the standardization of emergency training for “rescue squad personnel, policemen, firemen and ambulance attendants.” This led to the first nationally recognized and standardized curriculum for EMS, Emergency Medical Technician–Ambulance (EMT-A), published in 1969.

Ever since, a greatly improved EMS system evolved, seeking to improve survival through a chain of actions that starts hopefully with prevention and safety programs, but may end up with care in a hospital emergency room. In between, the blue and white, six-pointed EMS symbol called “the Star of Life” best illustrates the ideal components. It was originally designed by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Traditionally the logo is used as a stamp of identification for ambulances, paramedics, or other personnel such as firefighters trained in EMS. See the illustration accompanying this article for the six parts of EMS. Local FD’s are usually involved in the parts of the Star of Life illustration above in part three (early response) and part four (on scene care), and sometimes in parts five (care in transit) and six (transfer to definitive care).

The licensing of EMS personnel and services occurs at the state level and, for some certifications, at the local level. Each state can add or subtract levels as they see fit for their needs. The federal government identifies a model scope of practice, including minimum skills for Emergency Medical Responders (EMR’s), Emergency Medical Technicians (EMT’s), Advanced EMTs and Paramedics.

In California, there are generally five levels of certification: 1) EMR’s, with a minimum of 40 hours of training; 2) EMT’s, with a minimum of 120 hours of training including some clinical time; 3) Advanced EMT’s (AEMT’s), with a minimum of 88 more hours of training; 4) Paramedics, with an average of 1100 hours of training including much clinical time; and 4) Mobile Intensive Care Nurses (MICN’s), or Registered Nurses who have completed additional training in pre-hospital care and often serve in critical care roles such as air transport. Not all counties offer or support all of these levels of certification.

While states are able to set their own additional requirements for state certification, a quasi-national certification group exists in the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT). The NREMT offers national certification based on the NHTSA National Standard Curriculum for the levels of EMR, EMT, Advanced EMT and Paramedic.

There have been many people who have made contributions to the growth of modern EMS in Plumas County. In Part III of this series, we’ll look closer at some of the early key players and groups, including identifying the first Paramedic and the first Mobile Intensive Care Nurse to serve full-time here.

Fire Departments and Emergency Medical Services 101, Part III

In the first two parts of this series we reviewed both the roots of the fire service contribution to emergency medical care in the field (EMS), and its’ major evolution since the late1960’s. Let’s take a closer look at what happened in Plumas County after the creation and national publication of Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) training guidelines in 1969.

There were many people involved in the early years of improved EMS around our area, but space limitations require we focus on one who was arguably the most important. Quincy’s own Steve Tolen is at the center of the history of modern EMS in Plumas County. Born in San Francisco and raised in San Mateo, Steve originally thought he wanted to be a funeral director. “The primary interest stemmed from being present for a family during a time of need”, said Steve, “It actually had very little to do with the dead but more with the living.” At that time, a large percentage of the ambulances operating throughout the US were run by funeral homes.

Steve joined the US Navy in the 1960’s, and completed training through the Navy Hospital Corps, a program that was more extensive than U.S. Army Medic training at the time. After an honorable discharge, he moved to Chico and went to work at one of the local hospitals. The work included some ambulance service. “ I did not have a great deal of understanding about what the job entailed, but the more I learned the more I liked it,” said Steve.

He was part of a group in the early days of improved EMS in the 1970’s that operated what they called the “400 horsepower crash cart”. It was basically a pickup truck carrying a heart defibrillator unit and some drugs to help cardiac patients. The unit responded to all suspected cardiac calls in Chico until the first Paramedics were trained at Butte College.

Meanwhile in Plumas County several of the local fire departments that operated ambulances were getting out of that role, including Quincy FD. The reasons included the increased EMS regulations that were coming soon. “Fire Chief Andy Anderson recognized this, and sold the QFD Ambulance to Chico Ambulance Service in 1972,” said Steve. Plumas District Hospital at the time was not interested in operating the resource. 23 year-old Steve Tolen was tasked with moving to Quincy and serving as manager of the new service, based out of a local residence with his wife Marilyn, also an EMT.

At that time, from 1973-1976, only the ambulance would respond to vehicle accidents and EMS calls. Steve completed a vehicle accident extrication course in Los Angeles County in 1976, and the Quincy FD reengaged in providing rescue services. A fund-raiser was held to buy a Jaws of Life, and the QFD equipped a trailer that was towed behind a brush fire rig. “Nurse Anesthesiologist Sally Rosen taught the first EMT class based on the new curriculum through Lassen College in 1974-75,” said Steve. Students included members of the Portola and Quincy FD’s.

Steve and his wife staffed the ambulance 24/7 along with some per diem employees. The Chico Ambulance Service struggled to make it work financially, and briefly pulled the ambulance out of Quincy after a request for a subsidy was turned down. The sheriff and CHP commander immediately went to the Plumas County Board of Supervisors and requested that they take action to bring the ambulance back. The ambulance was returned to Quincy on the premise that a subsidy would be investigated. This never happened, and at that time in 1976 Plumas District Hospital took over the ambulance service.

Steve recruited the first known Paramedic to serve in the County in the 1980’s – Quincy’s own Robbie Cassou, currently serving as the Quincy Fire Chief. Robbie had met an MICN, Julie Yamanaka, when she served as an instructor in his Paramedic training program in LA County. They would later marry and move to Quincy after being recruited by Steve. Both worked at the Plumas District Hospital for many years, with Robbie eventually accepting a position at the Quincy FD and Julie continuing to work at PDH until her retirement a few years ago. Steve also became a Paramedic and worked at PDH for most of his career.

Today Steve continues to serve as the Chairman of the Plumas County Emergency Medical Care Committee (EMCC), a group that serves in an advisory capacity to the Board of Supervisors on ambulance services, emergency medical care, first aid practices, and training in CPR and Lifesaving techniques. The EMCC also provides information to the regional Nor Cal EMS Agency and the State EMS agency.

The Plumas County Fire Chiefs Association will be completing a more comprehensive history of EMS in Plumas County and giving it to the Plumas County Museum eventually. If you have any further information or photographs of the early days of improved EMS, please contact the author at tnforster@mac.com. In the next and final part of this series, we will review the level of emergency medical services provided in the field by each local FD, along with ambulance services.

In the first two parts of this series we reviewed both the roots of the fire service contribution to emergency medical care in the field (EMS), and its’ major evolution since the late1960’s. Let’s take a closer look at what happened in Plumas County after the creation and national publication of Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) training guidelines in 1969.

There were many people involved in the early years of improved EMS around our area, but space limitations require we focus on one who was arguably the most important. Quincy’s own Steve Tolen is at the center of the history of modern EMS in Plumas County. Born in San Francisco and raised in San Mateo, Steve originally thought he wanted to be a funeral director. “The primary interest stemmed from being present for a family during a time of need”, said Steve, “It actually had very little to do with the dead but more with the living.” At that time, a large percentage of the ambulances operating throughout the US were run by funeral homes.

Steve joined the US Navy in the 1960’s, and completed training through the Navy Hospital Corps, a program that was more extensive than U.S. Army Medic training at the time. After an honorable discharge, he moved to Chico and went to work at one of the local hospitals. The work included some ambulance service. “ I did not have a great deal of understanding about what the job entailed, but the more I learned the more I liked it,” said Steve.

He was part of a group in the early days of improved EMS in the 1970’s that operated what they called the “400 horsepower crash cart”. It was basically a pickup truck carrying a heart defibrillator unit and some drugs to help cardiac patients. The unit responded to all suspected cardiac calls in Chico until the first Paramedics were trained at Butte College.

Meanwhile in Plumas County several of the local fire departments that operated ambulances were getting out of that role, including Quincy FD. The reasons included the increased EMS regulations that were coming soon. “Fire Chief Andy Anderson recognized this, and sold the QFD Ambulance to Chico Ambulance Service in 1972,” said Steve. Plumas District Hospital at the time was not interested in operating the resource. 23 year-old Steve Tolen was tasked with moving to Quincy and serving as manager of the new service, based out of a local residence with his wife Marilyn, also an EMT.

At that time, from 1973-1976, only the ambulance would respond to vehicle accidents and EMS calls. Steve completed a vehicle accident extrication course in Los Angeles County in 1976, and the Quincy FD reengaged in providing rescue services. A fund-raiser was held to buy a Jaws of Life, and the QFD equipped a trailer that was towed behind a brush fire rig. “Nurse Anesthesiologist Sally Rosen taught the first EMT class based on the new curriculum through Lassen College in 1974-75,” said Steve. Students included members of the Portola and Quincy FD’s.

Steve and his wife staffed the ambulance 24/7 along with some per diem employees. The Chico Ambulance Service struggled to make it work financially, and briefly pulled the ambulance out of Quincy after a request for a subsidy was turned down. The sheriff and CHP commander immediately went to the Plumas County Board of Supervisors and requested that they take action to bring the ambulance back. The ambulance was returned to Quincy on the premise that a subsidy would be investigated. This never happened, and at that time in 1976 Plumas District Hospital took over the ambulance service.

Steve recruited the first known Paramedic to serve in the County in the 1980’s – Quincy’s own Robbie Cassou, currently serving as the Quincy Fire Chief. Robbie had met an MICN, Julie Yamanaka, when she served as an instructor in his Paramedic training program in LA County. They would later marry and move to Quincy after being recruited by Steve. Both worked at the Plumas District Hospital for many years, with Robbie eventually accepting a position at the Quincy FD and Julie continuing to work at PDH until her retirement a few years ago. Steve also became a Paramedic and worked at PDH for most of his career.

Today Steve continues to serve as the Chairman of the Plumas County Emergency Medical Care Committee (EMCC), a group that serves in an advisory capacity to the Board of Supervisors on ambulance services, emergency medical care, first aid practices, and training in CPR and Lifesaving techniques. The EMCC also provides information to the regional Nor Cal EMS Agency and the State EMS agency.

The Plumas County Fire Chiefs Association will be completing a more comprehensive history of EMS in Plumas County and giving it to the Plumas County Museum eventually. If you have any further information or photographs of the early days of improved EMS, please contact the author at tnforster@mac.com. In the next and final part of this series, we will review the level of emergency medical services provided in the field by each local FD, along with ambulance services.

Fire Departments and Emergency Medical Services 101, Part IV

In the first three parts of this series we reviewed the roots of the fire service contribution to emergency medical care in the field (EMS), the evolution in EMS nationally since the late 1960’s, and what happened in Plumas County. Finally, in this last part we’ll identify the various levels of field service provided by local government FD’s, and the local hospitals.

From the “50,000 foot” level, looking down on the County, everyone has access to advanced emergency medical care in the field. The difference lies in two main areas – the first and most important is how long it takes to get that service, and the second is at what cost. Each community may already be funding a certain level of EMS service, but it varies significantly. This is not unusual in rural areas.

Just as there is no law requiring a community to have a fire department, there is no requirement for a community to provide EMS. The requirements from various regulatory sources begin when the decision is made to provide such services.

Remember there are two main categories of EMS service levels in the field – Basic Life Support, or BLS, and Advanced Life Support, or ALS. In the case of FD’s, Basic Life Support refers to two levels of training. First Responders (soon to be called Emergency Medical Responders) are the basic level, or FR’s/EMR's, and the next level up are Emergency Medical Technicians Level I, or EMT-I. Next, ALS refers to Paramedics, often called “Medics” and also any Mobile Intensive Care Nurses, or MICN’s, trained at an even higher level. “ALS or BLS Transport” refers to ambulance services with that level of training and related tools.

In Plumas County, the following FD’s provide BLS level services, usually consisting of a mix of FR’s/EMR's and EMT’s: Sierra Valley, Portola, Eastern Plumas (also contracting to service C Road), Plumas Eureka, Long Valley, Greenhorn Creek, Quincy, Meadow Valley, Bucks Lake, La Porte, Indian Valley, and Crescent Mills. A few FD’s provide part-time ALS services, including Beckwourth, Graeagle, and West Almanor (also contracting to service Prattville). By “part-time” this means that while BLS is always provided at a minimum, but the provision of ALS depends on one or more Paramedics or MICN’s in the FD being available either on-duty or as a volunteer.

Finally, two FD’s provide full-time ALS services and also ALS or BLS transport services with ambulances – Peninsula Fire Protection District, also serving Hamilton Branch, and Chester FD. In all areas, each FD works with local hospitals or EMS helicopter services to transition from field care. There are three hospitals in Plumas County. Eastern Plumas Health Care in Portola and Plumas District Hospital in Quincy each operate ALS ambulance transport services, with a minimum staffing of one Paramedic and one EMT. Seneca Hospital in Chester does not provide ambulance service since Chester FD and Peninsula FD do.

Each EMS Provider will offer mutual aid to others as needed. All FD’s can access helicopter services that include ALS level care, but at a significant cost to the patient and/or insurance. Helicopters typically fly into the County from Chico, Reno, Susanville, or Truckee. Law enforcement may also provide or assist field EMS services at the BLS level, but this is not standardized. There are some officers who have EMT and other EMS training, but due to space limitations this is not being covered in this article.

And what about those areas that are outside of fire districts in our County? The closest EMS providers will be dispatched, but there will almost always be costs assessed through billing. Generally, as a community member we get the level of EMS service from our FD's we are funding through taxes or other means. This amount varies widely, and additional services are available to all but at a cost and possible extended arrival time. Space limitations again prevent a detailed review. You or your health care provider may also be responsible for ambulance billing.

In closing this series of columns on EMS, the Plumas County Fire Chiefs Association (PCFCA) is proud to announce that Steve Tolen of Quincy has been recognized with the first perpetual “Steve Tolen Leadership in EMS Award" [February of 2015]. This award will be presented each year by PCFCA to a deserving Plumas County EMS member, and not necessarily someone from a Fire Department - all EMS contributors will be considered. Please join us in congratulating Steve for his many decades of leadership in EMS! See Part III and the link below for more information on Steve.

In the first three parts of this series we reviewed the roots of the fire service contribution to emergency medical care in the field (EMS), the evolution in EMS nationally since the late 1960’s, and what happened in Plumas County. Finally, in this last part we’ll identify the various levels of field service provided by local government FD’s, and the local hospitals.

From the “50,000 foot” level, looking down on the County, everyone has access to advanced emergency medical care in the field. The difference lies in two main areas – the first and most important is how long it takes to get that service, and the second is at what cost. Each community may already be funding a certain level of EMS service, but it varies significantly. This is not unusual in rural areas.

Just as there is no law requiring a community to have a fire department, there is no requirement for a community to provide EMS. The requirements from various regulatory sources begin when the decision is made to provide such services.

Remember there are two main categories of EMS service levels in the field – Basic Life Support, or BLS, and Advanced Life Support, or ALS. In the case of FD’s, Basic Life Support refers to two levels of training. First Responders (soon to be called Emergency Medical Responders) are the basic level, or FR’s/EMR's, and the next level up are Emergency Medical Technicians Level I, or EMT-I. Next, ALS refers to Paramedics, often called “Medics” and also any Mobile Intensive Care Nurses, or MICN’s, trained at an even higher level. “ALS or BLS Transport” refers to ambulance services with that level of training and related tools.

In Plumas County, the following FD’s provide BLS level services, usually consisting of a mix of FR’s/EMR's and EMT’s: Sierra Valley, Portola, Eastern Plumas (also contracting to service C Road), Plumas Eureka, Long Valley, Greenhorn Creek, Quincy, Meadow Valley, Bucks Lake, La Porte, Indian Valley, and Crescent Mills. A few FD’s provide part-time ALS services, including Beckwourth, Graeagle, and West Almanor (also contracting to service Prattville). By “part-time” this means that while BLS is always provided at a minimum, but the provision of ALS depends on one or more Paramedics or MICN’s in the FD being available either on-duty or as a volunteer.

Finally, two FD’s provide full-time ALS services and also ALS or BLS transport services with ambulances – Peninsula Fire Protection District, also serving Hamilton Branch, and Chester FD. In all areas, each FD works with local hospitals or EMS helicopter services to transition from field care. There are three hospitals in Plumas County. Eastern Plumas Health Care in Portola and Plumas District Hospital in Quincy each operate ALS ambulance transport services, with a minimum staffing of one Paramedic and one EMT. Seneca Hospital in Chester does not provide ambulance service since Chester FD and Peninsula FD do.

Each EMS Provider will offer mutual aid to others as needed. All FD’s can access helicopter services that include ALS level care, but at a significant cost to the patient and/or insurance. Helicopters typically fly into the County from Chico, Reno, Susanville, or Truckee. Law enforcement may also provide or assist field EMS services at the BLS level, but this is not standardized. There are some officers who have EMT and other EMS training, but due to space limitations this is not being covered in this article.

And what about those areas that are outside of fire districts in our County? The closest EMS providers will be dispatched, but there will almost always be costs assessed through billing. Generally, as a community member we get the level of EMS service from our FD's we are funding through taxes or other means. This amount varies widely, and additional services are available to all but at a cost and possible extended arrival time. Space limitations again prevent a detailed review. You or your health care provider may also be responsible for ambulance billing.

In closing this series of columns on EMS, the Plumas County Fire Chiefs Association (PCFCA) is proud to announce that Steve Tolen of Quincy has been recognized with the first perpetual “Steve Tolen Leadership in EMS Award" [February of 2015]. This award will be presented each year by PCFCA to a deserving Plumas County EMS member, and not necessarily someone from a Fire Department - all EMS contributors will be considered. Please join us in congratulating Steve for his many decades of leadership in EMS! See Part III and the link below for more information on Steve.